White Paper by Lena Hull

Peer Reviewed by Kacee Doan, Christopher Timbreza

Origins of Psilocybin

Psilocybin has been present in the scientific community since the 1960s, but only recently has been considered for treatment of addiction. Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman was the first to extract psilocybin from Psilocybe mexicana in 1959 (Hoffman et al., 1959). Soon after this, in 1960, Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert conducted the controversial Harvard Psilocybin Project. This project was not entirely scientific; they tested 175 students, of which the majority said that they had learned something about themselves after taking psilocybin, and wanted to take it again. Later, Leary conducted tests on prisoners in Concord by giving them psilocybin then collecting qualitative data, and found a massive success rate. Prisoners were said to have very positive, “religious” experiences that inspired them to reform, something the prison system never did for them. Because of this, Learly proposed the use of psilocybin in the federal penal system as a sort of therapy but was denied (Leaman, 2011).

Regulation and Current Legal Status

Some minor studies concerning psilocybin were completed throughout the 1960s, but in 1970 psilocybin was categorized as a Schedule 1 drug under the The Federal Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (also known as the Controlled Substances Act), effective May 1st, 1971 (Gabay, 2013). According to the DEA, this meant that the drug was suspected to have a high potential for abuse, even under strict medical supervision (Drugs, 2017). After the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, psilocybin research stopped until 1999, when the FDA approved a study at John Hopkins School of Medicine (Simoneaux, 1999). Research and clinical interest has increased since then, and psilocybin is currency being tested for possible clinical uses. Currently, the FDA has designated psilocybin as a “Breakthrough Therapy” (Hale, 2020), which the FDA states is “...a process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s)” (Breakthrough, 2018). This means that for the first time in fifty years, the FDA has recognized that psilocybin is most likely an important drug that can be used in various clinical applications.

Pharmacology

There have been various studies on the psychopharmacology of psilocybin since 1999, though there is still a large gap in the research because of psilocybin’s legal status, making it difficult to access. After it is ingested, psilocybin is converted into psilocin through first pass metabolism (Passie et al., 2002).This psilocin acts on serotonergic pathways of the brain, mainly acting on receptor 5-HT2A as an agonist (Madsen et al., 2020). This means that it mimics the serotonin molecules that bind to 5-HT2A receptors so that the receptors’ neurons are constantly “on” and communicating with other neurons to influence brain functioning. More research needs to be done on psilocybin’s pharmacological activity however, as many drugs interact with 5-HT2A receptors and do not produce psychedelic effects, and we do not know exactly why (Blough et al., 2014). 5-HT2A receptors are an important part of visual processing, which may be why psilocybin produces hallucinations that are common to psychedelic drugs (Kometer et al., 2011). Increased activity of these receptors in the cerebral cortex as caused by psilocybin also causes heightened interconnectivity in the cortex, creating a large amount of unusual subjective effects typically associated with psychedelics (Petri et al., 2014).

Psilocybin as an Addiction Treatment

In terms of addiction, there have been two major studies where psilocybin was used to treat alcohol dependence and nicotine addiction, respectively. In both of these studies psilocybin therapy was only administered in the short-term.

In both studies, participants underwent psychological intervention in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy in the weeks prior to psilocybin therapy. During treatment with psilocybin, the alcohol dependence group took 0.3mg/kg of psilocybin in their first session and 0.4mg/kg in their second session; it is not noted how far apart these sessions took place. The nicotine addiction group took 20mg/70kg in their first session and 30mg/70kg in their second and third sessions, each two weeks apart from one another. Also, in both studies participants were screened for other signs of drug abuse as well as mental health disorders, as this therapy is not currently deemed as suitable for people with underlying mental illness on top of a history of addiction, or for those who are more severely addicted to illicit substances (Bogenschutz et al., 2015; Johnson, Garcia-Romeu & Griffiths, 2016).

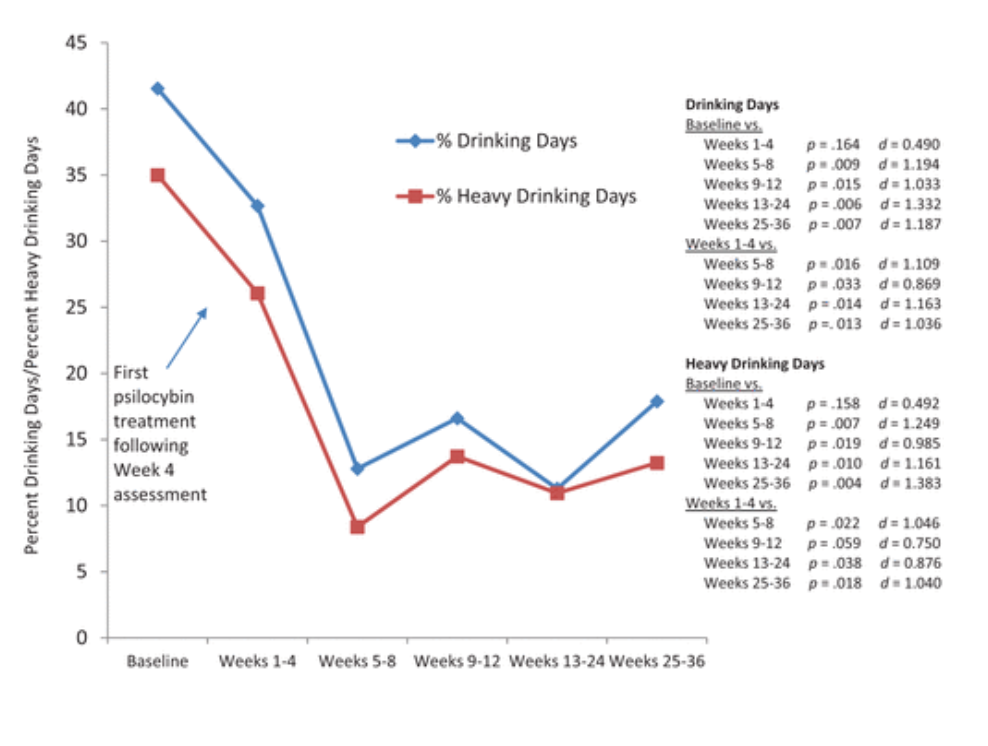

It is not currently known exactly how psilocybin works psychologically or physiologically to treat addiction, however, it does seem effective based on the two aforementioned studies. In the alcohol dependence study, “percent drinking days” went from about 41% before psilocybin therapy to just 12% afterwards, showing significant improvement. In the nicotine addiction study, 80% of the participants stayed abstinent when tested for nicotine consumption six months after psilocybin therapy and reported no persisting negative side effects, suggesting that psilocybin is useful as a nicotine-abstinence therapy.

On top of addiction treatment, 86.7% of the participants in the nicotine study rated their psilocybin experience as “among the five most personally meaningful of their lives” or as “among the five most spiritually significant experiences of their lives” (Garcia-Romeu & Griffiths, 2016, pp. 58). Neither studies reported long term negative side effects, but elevated blood pressure and heart rate, headache, nausea, IBS, and insomnia were reported as acute side effects, all occurring and subsiding within 24 hours of treatment.

Anecdotes

Though specific instances of study participants writing about their experiences are elusive, there are great accounts of self medication with psilocybin across the internet. The website https://www.mycomeditations.com/blog/ has a few accounts from users of psilocybin. A user from Mycomeditations writes: “The truth is, that mushrooms don’t ‘fix’ the problem. They do however offer a perspective shift. In my hundreds of psilocybin experiences one of, if not the most important lesson has been to sit patiently, observing the mental states rather than engaging in them” (n.d). Another person from the Facebook group “Psychedelic Society” writes: “Looked at myself in the mirror and I was looking into my eyes with unconditional love and acceptance. ‘Through the eyes of god’ is the only way I could describe it. My self love and therefore love for others has had a great positive shift” (2020).

Advocacy

On top of individual users, multiple healthcare, legal, and psychology professionals from the organization Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) research and advocate for the use of psychedelics, including psilocybin, in clinical settings. Their staff page at https://maps.org/about/staff lists the people involved in their organization. MAPS also has a page, https://integration.maps.org/, that lists multiple healthcare professionals who help people integrate their psychedelic experiences into their lives.

References

Blough, B. E., Landavazo, A., Decker, A. M., Partilla, J. S., Baumann, M. H., & Rothman, R. B. (2014). Interaction of psychoactive tryptamines with biogenic amine transporters and serotonin receptor subtypes. Psychopharmacology, 231(21), 4135-4144. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3557-7

Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P., & Strassman, R. J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(3), 289-299. doi:10.1177/0269881114565144

Bogenschutz, M. P. (2016). It’s time to take psilocybin seriously as a possible treatment for substance use disorders. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(1), 4–6. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1200060

Breakthrough Therapy. (2018, January 4). Retrieved June 17, 2020, from https://www.fda.gov/patients/fast-track-breakthrough-therapy-accelerated-approval-priority-review/breakthrough-therapy

Drugs of Abuse [PDF]. (2017). Washington, DC: Drug Enforcement Administration.

Gabay, M. (2013). The Federal Controlled Substances Act: Schedules and Pharmacy Registration. Hospital Pharmacy, 48(6), 473–474. doi: 10.1310/hpj4806-473

Hale, V. (n.d.). The FDA and Psychedelic Drug Development: Working Together to Make Medicines. Retrieved June 17, 2020, from https://maps.org/news/bulletin/articles/439-bulletin-spring-2020/8129-the-fda-and-psychedelic-drug-development-working-together-to-make-medicines

Hofmann, A., Heim, R., Brack, A., Kobel, H., Frey, A., Ott, H., … Troxler, F. (1959). Psilocybin und Psilocin, zwei psychotrope Wirkstoffe aus mexikanischen Rauschpilzen. Helvetica Chimica Acta, 42(5), 1557–1572. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19590420518

Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2016). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(1), 55-60. doi:10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135

Kometer, M., Cahn, B. R., Andel, D., Carter, O. L., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2011). The 5-HT2A/1A Agonist Psilocybin Disrupts Modal Object Completion Associated with Visual Hallucinations. Biological Psychiatry, 69(5), 399-406. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.002

Leaman, K. (2011, November 4). PDF. West Lafayette.

Madsen, M. K., Fisher, P. M., Stenbæk, D. S., Kristiansen, S., Burmester, D., Lehel, S., . . . Knudsen, G. M. (2020). A single psilocybin dose is associated with long-term increased mindfulness, preceded by a proportional change in neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 71-80. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.02.001

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. (2020). Retrieved September 08, 2020, from https://maps.org/

Osborne, E. (n.d.). My Struggles, Depression, and My Work With Psilocybin [Web log post]. Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://www.mycomeditations.com/my-struggles-depression-and-my-work-with-psilocybin/

Passie, T., Seifert, J., Schneider, U., & Emrich, H. M. (2002). The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addiction Biology, 7(4), 357-364. doi:10.1080/1355621021000005937

Petri, G., Expert, P., Turkheimer, F., Carhart-Harris, R., Nutt, D., Hellyer, P. J., & Vaccarino, F. (2014). Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 11(101). doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.0873

Porter, D. (2020, June 18). [Facebook comment from Facebook group Psychadelic Society].

Psychedelic Integration List. (n.d.). Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://integration.maps.org/

Simoneaux, R. (2019). The Potential of Psilocybin Administration in Terminal Cancer Patients. Oncology Times, 41(13), 14-15. doi:10.1097/01.cot.0000574916.46844.cf

Staff. (n.d.). Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://maps.org/about/staff